V

THE WAR OF INDEPENDENCE, 1775-1783

Books for Study and Reading

References.--Fiske's War of Independence; Higginson's

Larger History, 249-293; McMaster's With the

Fathers.

Home Readings.--Scudder's Washington; Holmes's

Grandmother's Story of Bunker Hill; Cooper's Lionel

Lincoln (Bunker Hill); Cooper's Spy (campaigns around

New York); Cooper's Pilot (the war on the sea); Drake's

Burgoyne's Invasion; Coffin's Boys of '76; Abbot's

Blue Jackets of '76; Abbot's Paul Jones, Lossing's

Two Spies.

CHAPTER 14

BUNKER HILL TO TRENTON

Advantages of the British.

133. Advantages of the British.--At first sight it seems

as if the Americans were very foolish to fight the British. There

were five or six times as many people in the British Isles as there

were in the continental colonies. The British government had a

great standing army. The Americans had no regular army. The British

government had a great navy. The Americans had no navy. The British

government had quantities of powder, guns, and clothing, while the

Americans had scarcely any military stores of any kind. Indeed,

there were so few guns in the colonies that one British officer

thought if the few colonial gunsmiths could be bribed to go away,

the Americans would have no guns to fight with after a few months

of warfare.

GRAND UNION FLAG.

Hoisted at Cambridge, January, 1776. The British Union and thirteen

stripes.

Advantages of the Americans.

134. Advantages of the Americans.--All these things were

clearly against the Americans. But they had some advantages on

their side. In the first place, America was a long way off from

Europe. It was very difficult and very costly to send armies to

America, and very difficult and very costly to feed the soldiers

when they were fighting in America. In the second place, the

Americans usually fought on the defensive and the country over

which the armies fought was made for defense. In New England hill

succeeded hill. In the Middle states river succeeded river. In the

South wilderness succeeded wilderness. In the third place, the

Americans had many great soldiers. Washington, Greene, Arnold,

Morgan, and Wayne were better soldiers than any in the British

army.

The Loyalists.

135. Disunion among the Americans.--We are apt to think

of the colonists as united in the contest with the British. In

reality the well-to-do, the well-born, and the well-educated

colonists were as a rule opposed to independence. The opponents of

the Revolution were strongest in the Carolinas, and were weakest in

New England.

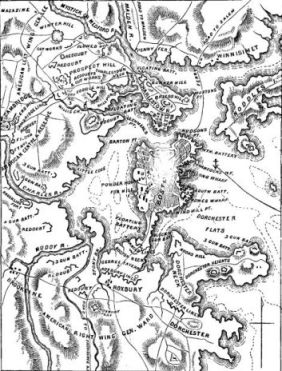

THE SIEGE OF BOSTON.

Boston and neighborhood, 1775-76.

Importance of Dorchester and Charlestown.

136. Siege of Boston.--It was most fortunate that the

British army was at Boston when the war began, for Boston was about

as bad a place for an army as could be found. In those days Boston

was hardly more than an island connected with the mainland by a

strip of gravel. Gage built a fort across this strip of ground. The

Americans could not get in. But they built a fort at the landward

end, and the British could not get out. On either side of Boston

was a similar peninsula. One of these was called Dorchester

Heights; the other was called Charlestown. Both overlooked Boston.

To hold that town, Gage must possess both Dorchester and

Charlestown. If the Americans could occupy only one of these, the

British would have to abandon Boston. At almost the same moment

Gage made up his mind to seize Dorchester, and the Americans

determined to occupy the Charlestown hills. The Americans moved

first, and the first battle was fought for the Charlestown

hills.

[Illustration: A POWDER-HORN USED AT BUNKER HILL.]

Battle of Bunker Hill, 1775. Higginson,

183-188; McMaster, 129-130.

137. Bunker Hill, June 17, 1775.--When the seamen on the

British men-of-war waked up on the morning of June 17, the first

thing they saw was a redoubt on the top of one of the Charlestown

hills. The ships opened fire. But in spite of the balls Colonel

Prescott walked on the top of the breastwork while his men went on

digging. Gage sent three or four thousand men across the Charles

River to Charlestown to drive the daring Americans away. It took

the whole morning to get them to Charlestown, and then they had to

eat their dinner. This delay gave the Americans time to send aid to

Prescott. Especially went Stark and his New Hampshire men, who

posted themselves behind a breastwork of fence rails and hay. At

last the British soldiers marched to the attack. When they came

within good shooting distance, Prescott gave the word to fire. The

British line stopped, hesitated, broke, and swept back. Again the

soldiers marched to the attack, and again they were beaten back.

More soldiers came from Boston, and a third time a British line

marched up the hill. This time it could not be stopped, for the

Americans had no more powder. They had to give up the hill and

escape as well as they could. One-half of the British soldiers

actually engaged in the assaults were killed or wounded. The

Americans were defeated. But they were encouraged and were willing

to sell Gage as many hills as he wanted at the same price.

[Illustration: FACSIMILE OF A REVOLUTIONARY POSTER.]

Washington takes command of the army, 1775.

Higginson, 188-193.

Seizure of Ticonderoga and Crown Point.

Evacuation of Boston, 1776.

138. Washington in Command, July, 1775.--The Continental

Congress was again sitting at Philadelphia. It took charge of the

defense of the colonies. John Adams named Washington for

commander-in-chief, and he was elected. Washington took command of

the army on Cambridge Common, July 3, 1775. He found everything in

confusion. The soldiers of one colony were jealous of the soldiers

of other colonies. Officers who had not been promoted were jealous

of those who had been promoted. In the winter the army had to be

made over. During all this time the people expected Washington to

fight. But he had not powder enough for half a battle. At last he

got supplies in the following way. In the spring of 1775 Ethan

Allen and his Green Mountain Boys, with the help of the people of

western Massachusetts and Connecticut, had captured Ticonderoga and

Crown Point. These forts were filled with cannon and stores left

from the French campaigns. Some of the cannon were now dragged by

oxen over the snow and placed in the forts around Boston. Captain

Manley, of the Massachusetts navy, captured a British brig loaded

with powder. Washington now could attack. He seized and held

Dorchester Heights. The British could no longer stay in Boston.

They went on board their ships and sailed away (March, 1776).

[Illustration: SITE OF TICONDEROGA.]

The Canada expedition, 1775-76.

Assault on Quebec.

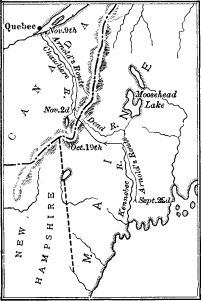

139. Invasion of Canada, 1775-76.--While the siege of

Boston was going on, the Americans undertook the invasion of

Canada. There were very few regular soldiers in Canada in 1775, and

the Canadians were not likely to fight very hard for their British

masters. So the leaders in Congress thought that if an American

force should suddenly appear before Quebec, the town might

surrender. Montgomery, with a small army, was sent to capture

Montreal and then to march down the St. Lawrence to Quebec.

Benedict Arnold led another force through the Maine woods. After

tremendous exertions and terrible sufferings he reached Quebec. But

the garrison had been warned of his coming. He blockaded the town

and waited for Montgomery. The garrison was constantly increased,

for Arnold was not strong enough fully to blockade the town. At

last Montgomery arrived. At night, amidst a terrible snowstorm,

Montgomery and Arnold led their brave followers to the attack. They

were beaten back with cruel loss. Montgomery was killed, and Arnold

was severely wounded. In the spring of 1776 the survivors of this

little band of heroes were rescued--at the cost of the lives of

five thousand American soldiers.

ARNOLD'S MARCH.

Strength of Charleston.

Fort Moultrie.

Attack on Fort Moultrie, 1776.

Success of the defense

140. British Attack on Charleston, 1776.--In June 1776 a

British fleet and army made an attack on Charleston, South

Carolina. This town has never been taken by attack from the sea.

Sand bars guard the entrance of the harbor and the channels through

these shoals lead directly to the end of Sullivan's Island. At that

point the Americans built a fort of palmetto logs and sand. General

Moultrie commanded at the fort and it was named in his honor, Fort

Moultrie. The British fleet sailed boldly in, but the balls from

the ships' guns were stopped by the soft palmetto logs. At one time

the flag was shot away and fell down outside the fort. But Sergeant

Jasper rushed out, seized the broken staff, and again set it up on

the rampart. Meantime, General Clinton had landed on an island and

was trying to cross with his soldiers to the further end of

Sullivan's Island. But the water was at first too shoal for the

boats. The soldiers jumped overboard to wade. Suddenly the water

deepened, and they had to jump aboard to save themselves from

drowning. All this time Americans were firing at them from the

beach. General Clinton ordered a retreat. The fleet also sailed

out--all that could get away--and the whole expedition was

abandoned.

[Illustration: GENERAL MOULTRIE.]

Defense of New York, 1776.

Battle of Long Island, 1776.

Escape of the Americans.

141. Long Island and Brooklyn Heights, 1776.--The very

day that the British left Boston, Washington ordered five regiments

to New York. For he well knew that city would be the next point of

attack. But he need not have been in such a hurry. General Howe,

the new British commander-in-chief, sailed first to Halifax and did

not begin the campaign in New York until the end of August. He then

landed his soldiers on Long Island and prepared to drive the

Americans away. Marching in a round-about way, he cut the American

army in two and captured one part of it. This brought him to the

foot of Brooklyn Heights. On the top was a fort. Probably Howe

could easily have captured it. But he had led in the field at

Bunker Hill and had had enough of attacking forts defended by

Americans. So he stopped his soldiers--with some difficulty. That

night the wind blew a gale, and the next day was foggy. The British

fleet could not sail into the East River. Skillful fishermen safely

ferried the rest of the American army across to New York. When at

length the British marched to the attack, there was no one left in

the fort on Brooklyn Heights.

Retreat from New York.

Washington crosses the Delaware.

142. From the Hudson to the Delaware, 1776.--Even now

with his splendid fleet and great army Howe could have captured the

Americans. But he delayed so long that Washington got away in

safety. Washington's army was now fast breaking up. Soldiers

deserted by the hundreds. A severe action at White Plains only

delayed the British advance. The fall of Fort Washington on the end

of Manhattan Island destroyed all hope of holding anything near New

York. Washington sent one part of his army to secure the Highlands

of the Hudson. With the other part he retired across New Jersey to

the southern side of the Delaware River. The end of the war seemed

to be in sight. In December, 1776, Congress gave the sole direction

of the war to Washington and then left Philadelphia for a place of

greater safety.

Battle of Trenton, 1776. Higginson, 203;

Hero Tales, 45-55

143. Trenton, December 26, 1776.--Washington did not give

up. On Christmas night, 1776, he crossed the Delaware with a

division of his army. A violent snowstorm was raging, the river was

full of ice. But Washington was there in person, and the soldiers

crossed. Then the storm changed to sleet and rain. But on the

soldiers marched. When the Hessian garrison at Trenton looked about

them next morning they saw that Washington and Greene held the

roads leading inland from the town. Stark and a few soldiers--among

them James Monroe--held the bridge leading over the Assanpink to

the next British post. A few horsemen escaped before Stark could

prevent them. But all the foot soldiers were killed or captured. A

few days later nearly one thousand prisoners marched through

Philadelphia. They were Germans, who had been sold by their rulers

to Britain's king to fight his battles. They were called Hessians

by the Americans because most of them came from the little German

state of Hesse Cassel.

[Illustration: Battle of Trenton.]

[Illustration: Battle of Princeton.]

Battle of Princeton, 1777. Source-Book,

149-151.

144. Princeton, January, 1777.--Trenton saved the

Revolution by giving the Americans renewed courage. General Howe

sent Lord Cornwallis with a strong force to destroy the Americans.

Washington with the main part of his army was now encamped on the

southern side of the Assanpink. Cornwallis was on the other bank at

Trenton. Leaving a few men to keep up the campfires, and to throw

up a slight fort by the bridge over the stream, Washington led his

army away by night toward Princeton. There he found several

regiments hastening to Cornwallis. He drove them away and led his

army to the highlands of New Jersey where he would be free from

attack. The British abandoned nearly all their posts in New Jersey

and retired to New York.

CHAPTER 15

THE GREAT DECLARATION AND THE FRENCH ALLIANCE

Rising spirit of independence, 1775-76.

145. Growth of the Spirit of Independence.--The year 1776

is even more to be remembered for the doings of Congress than it is

for the doings of the soldiers. The colonists loved England. They

spoke of it as home. They were proud of the strength of the British

empire, and glad to belong to it. But their feelings rapidly

changed when the British government declared them to be rebels,

made war upon them, and hired foreign soldiers to kill them. They

could no longer be subjects of George III. That was clear enough.

They determined to declare themselves to be independent. Virginia

led in this movement, and the chairman of the Virginia delegation

moved a resolution of independence. A committee was appointed to

draw up a declaration.

[Illustration: FIRST UNITED STATES FLAG. Adopted by Congress in

1777.]

The Great Declaration, adopted July 4, 1776.

Higginson, 194-201; McMaster, 131-135;

Source-Book, 147-149.

Signing of the Declaration, August 2, 1776.

146. The Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1776.--The

most important members of this committee were Benjamin Franklin,

John Adams, and Thomas Jefferson. Of these Jefferson was the

youngest, and the least known. But he had already drawn up a

remarkable paper called A Summary View of the Rights of British

America. The others asked him to write out a declaration. He

sat down without book or notes of any kind, and wrote out the Great

Declaration in almost the same form in which it now stands. The

other members of the committee proposed a few changes, and then

reported the declaration to Congress. There was a fierce debate in

Congress over the adoption of the Virginia resolution for

independence. But finally it was adopted. Congress then examined

the Declaration of Independence as reported by the committee. It

made a few changes in the words and struck out a clause condemning

the slave-trade. The first paragraph of the Declaration contains a

short, clear statement of the basis of the American system of

government. It should be learned by heart by every American boy and

girl, and always kept in mind. The Declaration was adopted on July

4, 1776. A few copies were printed on July 5, with the signatures

of John Hancock and Charles Thompson, president and secretary of

Congress. On August 2, 1776, the Declaration was signed by the

members of Congress.

[Illustration: Battle of Brandywine.]

Battle of Brandywine 1777. McMaster,

137-138.

Battle of Germantown, 1777.

147. The Loss of Philadelphia, 1777.--For some months

after the battle of Princeton there was little fighting. But in the

summer of 1777, Howe set out to capture Philadelphia. Instead of

marching across New Jersey, he placed his army on board ships, and

sailed to Chesapeake Bay. As soon as Washington learned what Howe

was about, he marched to Chad's Ford, where the road from

Chesapeake Bay to Philadelphia crossed Brandywine Creek. Howe moved

his men as if about to attempt to cross the ford. Meantime he sent

Cornwallis with a strong force to cross the creek higher up.

Cornwallis surprised the right wing of the American army, drove it

back, and Washington was compelled to retreat. Howe occupied

Philadelphia and captured the forts below the city. Washington

tried to surprise a part of the British army which was posted at

Germantown. But accidents and mist interfered. The Americans then

retired to Valley Forge--a strong place in the hills not far from

Philadelphia.

The army at Valley Forge, 1777-78.

[Illustration: "The Glorious WASHINGTON and GATES." FROM

TITLE-PAGE OF AN ALMANAC OF 1778. To show condition of

wood-engraving in the Revolutionary era.]

Baron Steuben.

148. The Army at Valley Forge, 1777-78.--The sufferings

of the soldiers during the following winter can never be

overstated. They seldom had more than half enough to eat. Their

clothes were in rags. Many of them had no blankets. Many more had

no shoes. Washington did all he could do for them. But Congress had

no money and could not get any. At Valley Forge the soldiers were

drilled by Baron Steuben, a Prussian veteran. The army took the

field in 1778, weak in numbers and poorly clad. But what soldiers

there were were as good as any soldiers to be found anywhere in the

world. During that winter, also, an attempt was made to dismiss

Washington from chief command, and to give his place to General

Gates. But this attempt ended in failure.

Burgoyne's campaign, 1777. Eggleston,

178-179; McMaster, 139-140; Source-Book, 154-157.

Schuyler and Gates.

149. Burgoyne's March to Saratoga, 1777.--While Howe was

marching to Philadelphia, General Burgoyne was marching southward

from Canada. It had been intended that Burgoyne and Howe should

seize the line of the Hudson and cut New England off from the other

states. But the orders reached Howe too late, and he went southward

to Philadelphia. Burgoyne, on his part, was fairly successful at

first, for the Americans abandoned post after post. But when he

reached the southern end of Lake Champlain, and started on his

march to the Hudson, his troubles began. The way ran through a

wilderness. General Schuyler had had trees cut down across its

woodland paths and had done his work so well that it took Burgoyne

about a day to march a mile and a half. This gave the Americans

time to gather from all quarters and bar his southward way. But

many of the soldiers had no faith in Schuyler and Congress gave the

command to General Horatio Gates.

Battle of Bennington, 1777. Hero Tales,

59-67.

150. Bennington, 1777.--Burgoyne had with him many

cavalrymen. But they had no horses. The army, too, was sadly in

need of food. So Burgoyne sent a force of dismounted dragoons to

Bennington in southern Vermont to seize horses and food. It

happened, however, that General Stark, with soldiers from New

Hampshire, Vermont, and western Massachusetts, was nearer

Bennington than Burgoyne supposed. They killed or captured all the

British soldiers. They then drove back with great loss a second

party which Burgoyne had sent to support the first one.

Battle of Oriskany, 1777.

151. Oriskany, 1777.--Meantime St. Leger, with a large

body of Indians and Canadian frontiersmen, was marching to join

Burgoyne by the way of Lake Ontario and the Mohawk Valley. Near the

site of the present city of Rome in New York was Fort Schuyler,

garrisoned by an American force. St. Leger stopped to besiege this

fort. The settlers on the Mohawk marched to relieve the garrison

and St. Leger defeated them at Oriskany. But his Indians now grew

tired of the siege, especially when they heard that Arnold with a

strong army was coming. St. Leger marched back to Canada and left

Burgoyne to his fate.

First battle of Freeman's Farm, 1777.

Second battle of Freeman's Farm, 1777.

Surrender of the British at Saratoga, 1777.

152. Saratoga, 1777.--Marching southward, on the western

side of the Hudson, Burgoyne and his army came upon the Americans

in a forest clearing called Freeman's Farm. Led by Daniel Morgan

and Benedict Arnold the Americans fought so hard that Burgoyne

stopped where he was and fortified the position. This was on

September 19. The American army posted itself near by on Bemis'

Heights. For weeks the two armies faced each other. Then, on

October 7, the Americans attacked. Again Arnold led his men to

victory. They captured a fort in the centre of the British line,

and Burgoyne was obliged to retreat. But when he reached the

crossing place of the Hudson, to his dismay he found a strong body

of New Englanders with artillery on the opposite bank. Gates had

followed the retiring British, and soon Burgoyne was practically

surrounded. His men were starving, and on October 17 he

surrendered.

The Treaty of Alliance, 1778.

153. The French Alliance, 1778.--Burgoyne's defeat made

the French think that the Americans would win their independence.

So Dr. Franklin, who was at Paris, was told that France would

recognize the independence of the United States, would make

treaties with the new nation, and give aid openly. Great Britain at

once declared war on France. The French lent large sums of money to

the United States. They sent large armies and splendid fleets to

America. Their aid greatly shortened the struggle for independence.

But the Americans would probably have won without French aid.

The British leave Philadelphia 1778.

Battle of Monmouth, 1778.

154. Monmouth, 1778.--The first result of the French

alliance was the retreat of the British from Philadelphia to New

York. As Sir Henry Clinton, the new British commander, led his army

across the Jerseys, Washington determined to strike it a blow. This

he did near Monmouth. The attack was a failure, owing to the

treason of General Charles Lee, who led the advance. Washington

reached the front only in time to prevent a dreadful disaster. But

he could not bring about victory, and Clinton seized the first

moment to continue his march to New York. There were other

expeditions and battles in the North. But none of these had any

important effect on the outcome of the war.

[Illustration: Clark's Campaign 1777-1778]

Clark's conquest of the Northwest, 1778-79. Hero

Tales, 31-41.

155. Clark's Western Campaign, 1778-79.--The Virginians

had long taken great interest in the western country. Their hardy

pioneers had crossed the mountains and begun the settlement of

Kentucky. The Virginians now determined to conquer the British

posts in the country northwest of the Ohio. The command was given

to George Rogers Clark. Gathering a strong band of hardy

frontiersmen he set out on his dangerous expedition. He seized the

posts in Illinois, and Vincennes surrendered to him. Then the

British governor of the Northwest came from Detroit with a large

force and recaptured Vincennes. Clark set out from Illinois to

surprise the British. It was the middle of the winter. In some

places the snow lay deep on the ground. Then came the early floods.

For days the Americans marched in water up to their waists. At

night they sought some little hill where they could sleep on dry

ground. Then on again through the flood. They surprised the British

garrison at Vincennes and forced it to surrender. That was the end

of the contest for the Northwest.

[Illustration: WEST POINT IN 1790.]

Benedict Arnold.

His treason, 1780 Higginson, 209-211; McMaster,

144

156. Arnold and André, 1780.--Of all the leaders

under Washington none was abler in battle than Benedict Arnold.

Unhappily he was always in trouble about money. He was distrusted

by Congress and was not promoted. At Saratoga he quarrelled with

Gates and was dismissed from his command. Later he became military

governor of Philadelphia and was censured by Washington for his

doings there. He then secured the command of West Point and offered

to surrender the post to the British. Major André, of

Clinton's staff, met Arnold to arrange the final details. On his

return journey to New York André was arrested and taken

before Washington. The American commander asked his generals if

André was a spy. They replied that André was a spy,

and he was hanged. Arnold escaped to New York and became a general

in the British army.

CHAPTER 16

INDEPENDENCE

Invasion of the South.

Capture of Charleston, 1780.

157. Fall of Charleston, 1780.--It seemed quite certain

that Clinton could not conquer the Northern states with the forces

given him. In the South there were many loyalists. Resistance might

not be so stiff there. At all events Clinton decided to attempt the

conquest of the South. Savannah was easily seized (1778), and the

French and Americans could not retake it (1779). In the spring of

1780, Clinton, with a large army, landed on the coast between

Savannah and Charleston. He marched overland to Charleston and

besieged it from the land side. The Americans held out for a long

time. But they were finally forced to surrender. Clinton then

sailed back to New York, and left to Lord Cornwallis the further

conquest of the Carolinas.

Battle of Camden, 1780.

158. Gates's Defeat at Camden, 1780.--Cornwallis had

little trouble in occupying the greater part of South Carolina.

There was no one to oppose him, for the American army had been

captured with Charleston. Another small army was got together in

North Carolina and the command given to Gates, the victor at

Saratoga. One night both Gates and Cornwallis set out to attack the

other's camp. The two armies met at daybreak, the British having

the best position. But this really made little difference, for

Gates's Virginia militiamen ran away before the British came within

fighting distance. The North Carolina militia followed the

Virginians. Only the regulars from Maryland and Delaware were left.

They fought on like heroes until their leader, General John De

Kalb, fell with seventeen wounds. Then the survivors surrendered.

Gates himself had been carried far to the rear by the rush of the

fleeing militia.

Battle of King's Mountain, 1780. Hero Tales,

71-78.

159. King's Mountain, October, 1780.--Cornwallis now

thought that resistance surely was at an end. He sent an expedition

to the settlements on the lower slopes of the Alleghany Mountains

to get recruits, for there were many loyalists in that region.

Suddenly from the mountains and from the settlements in Tennessee

rode a body of armed frontiersmen. They found the British soldiers

encamped on the top of King's Mountain. In about an hour they had

killed or captured every British soldier.

[Illustration: THE SOUTHERN CAMPAIGNS.]

General Greene.

Morgan's victory of the Cowpens, 1781.

160. The Cowpens, 1781.--General Greene was now sent to

the South to take charge of the resistance to Cornwallis. A great

soldier and a great organizer Greene found that he needed all his

abilities. His coming gave new spirit to the survivors of Gates's

army. He gathered militia from all directions and marched toward

Cornwallis. Dividing his army into two parts, he sent General

Daniel Morgan to threaten Cornwallis from one direction, while he

threatened him from another direction. Cornwallis at once became

uneasy and sent Tarleton to drive Morgan away, but the hero of many

hard-fought battles was not easily frightened. He drew up his

little force so skillfully that in a very few minutes the British

were nearly all killed or captured.

[Illustration: GENERAL MORGAN THE HERO OF COWPENS.]

Greene's retreat.

The Battle of Guilford, 1781.

161. The Guilford Campaign, 1781.--Cornwallis now made a

desperate attempt to capture the Americans, but Greene and Morgan

joined forces and marched diagonally across North Carolina.

Cornwallis followed so closely that frequently the two armies

seemed to be one. When, however, the river Dan was reached, there

was an end of marching, for Greene had caused all the boats to be

collected at one spot. His men crossed and kept the boats on their

side of the river. Soon Greene found himself strong enough to cross

the river again to North Carolina. He took up a very strong

position near Guilford Court House. Cornwallis attacked. The

Americans made a splendid defense before Greene ordered a retreat,

and the British won the battle of Guilford. But their loss was so

great that another victory of the same kind would have destroyed

the British army. As it was, Greene had dealt it such a blow that

Cornwallis left his wounded at Guilford and set out as fast as he

could for the seacoast. Greene pursued him for some distance and

then marched southward to Camden.

Greene's later campaigns, 1871-83.

162. Greene's Later Campaigns.--At Hobkirk's Hill, near

Camden, the British soldiers who had been left behind by Cornwallis

attacked Greene. But he beat them off and began the siege of a fort

on the frontier of South Carolina. The British then marched up from

Charleston, and Greene had to fall back. Then the British marched

back to Charleston and abandoned the interior of South Carolina to

the Americans. There was only one more battle in the South--at

Eutaw Springs. Greene was defeated there, too, but the British

abandoned the rest of the Carolinas and Georgia with the exception

of Savannah and Charleston. In these wonderful campaigns with a few

good soldiers Greene had forced the British from the Southern

states. He had lost every battle. He had won every campaign.

Lafayette and Cornwallis, 1781.

163. Cornwallis in Virginia, 1781.--There were already

two small armies in Virginia,--the British under Arnold, the

Americans under Lafayette. Cornwallis now marched northward from

Wilmington and added the troops in Virginia to his own force;

Arnold he sent to New York. Cornwallis then set out to capture

Lafayette and his men. Together they marched from salt water across

Virginia to the mountains--and then they marched back to salt water

again. Cornwallis had called Lafayette "the boy" and had declared

that "the boy should not escape him." Finally Cornwallis fortified

Yorktown, and Lafayette settled down at Williamsburg. And there

they still were in September, 1781.

The French at Newport, 1780.

Plans of the allies, 1781.

164. Plans of the Allies.--In 1780 the French government

had sent over a strong army under Rochambeau. It was landed at

Newport. It remained there a year to protect the vessels in which

it had come from France from capture by a stronger British fleet

that had at once appeared off the mouth of the harbor. Another

French fleet and another French army were in the West Indies. In

the summer of 1781 it became possible to unite all these French

forces, and with the Americans to strike a crushing blow at the

British. Just at this moment Cornwallis shut himself up in

Yorktown, and it was determined to besiege him there.

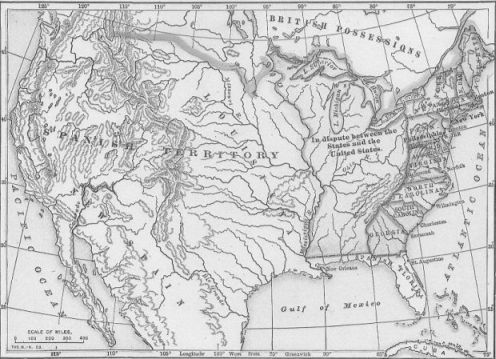

THE UNITED STATES IN 1783.

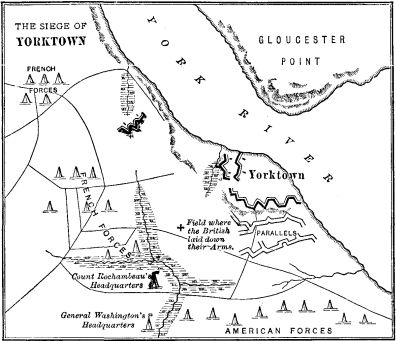

The Siege of Yorktown.

The march to the Chesapeake.

Combat between the French and the British fleets.

Surrender of Yorktown, October 19, 1781. Higginson,

211-212.

165. Yorktown, September-October, 1781.--Rochambeau led

his men to New York and joined the main American army. Washington

now took command of the allied forces. He pretended that he was

about to attack New York and deceived Clinton so completely that

Clinton ordered Cornwallis to send some of his soldiers to New

York. But the allies were marching southward through Philadelphia

before Clinton realized what they were about. The French West India

fleet under De Grasse reached one end of the Chesapeake Bay at the

same time the allies reached the other end. The British fleet

attacked it and was beaten off. There was now no hope for

Cornwallis. No help could reach him by sea. The soldiers of the

allies outnumbered him two to one. On October 17, 1781, four years

to a day since the surrender of Burgoyne, a drummer boy appeared on

the rampart of Yorktown and beat a parley. Two days later the

British soldiers marched out to the good old British tune of "The

world turned upside down," and laid down their arms.

Treaty of Peace, 1783.

166. Treaty of Peace, 1783.--This disaster put an end to

British hopes of conquering America. But it was not until

September, 1783, that Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and John Jay

brought the negotiations for peace to an end. Great Britain

acknowledged the independence of the United States. The territory

of the United States was defined as extending from the Great Lakes

to the thirty-first parallel of latitude and from the Atlantic to

the Mississippi. Spain had joined the United States and France in

the war. Spanish soldiers had conquered Florida, and Spain kept

Florida at the peace. In this way Spanish Florida and Louisiana

surrounded the United States on the south and the west. British

territory bounded the United States on the north and the

northeast.

QUESTIONS AND TOPICS

CHAPTER 14

§§ 134-136.--a. Compare the advantages of the

British and the Americans. Which side had the greater

advantages?

b. Explain the influence of geographical surroundings

upon the war.

c. Why were there so many loyalists?

§§ 137-139.--a. Mold or draw a map of Boston

and vicinity and explain by it the important points of the

siege.

b. Who won the battle of Bunker Hill? What were the

effects of the battle upon the Americans? Upon the British?

c. Why was Washington appointed to chief command?

d. What were the effects of the seizure of Ticonderoga on

the siege of Boston?

§§ 140, 141.--a. Why did Congress determine to

attack Canada? b. Follow the routes of the two invading

armies. What was the result of the expedition?

c. Describe the harbor of Charleston. Why did the British

attack at this point?

d. What was the result of this expedition?

§§ 142, 143.--a. What advantage would the

occupation of New York give the British?

b. Describe the Long Island campaign.

c. Why did Congress give Washington sole direction of the

war? Who had directed the war before?

§§ 144, 145.--a. Describe the battle of

Trenton. Why is it memorable?

b. Who were the Hessians?

c. At the close of January, 1777, what places were held

by the British?

CHAPTER 15

§§146, 147.--a. What had been the feeling of

most of the colonists toward England? Why had this feeling

changed?

b. Why was Jefferson asked to write the Declaration?

c. What great change was made by Congress in the

Declaration? Why?

d. What truths are declared to be self-evident? Are they

still self-evident?

e. What is declared to be the basis of government? Is it

still the basis of government?

f. When was the Declaration adopted? When signed?

§§ 148, 149.--a. Describe Howe's campaign of

1777.

b. What valuable work was done at Valley Forge?

§§ 150-153.--a. What was the object of

Burgoyne's campaign? Was the plan a wise one from the British point

of view?

b. What do you think of the justice of removing

Schuyler?

c. How did the battle of Bennington affect the campaign?

What was the effect of St. Leger's retreat to Canada?

d. Describe Arnold's part in the battles near

Saratoga.

§§ 154, 155.--a. What was the effect of

Burgoyne's surrender on Great Britain? On France? On America?

b. What were the results of the French alliance?

c. Describe the battle of Monmouth. Who was Charles

Lee?

§ 156.--a. Describe Clark's expedition and mark on a

map the places named. b. How did this expedition affect the

later growth of the United States?

§ 157.--a. Describe Arnold's career as a soldier to

1778. b. What is treason? c. Was there the least

injustice in the treatment of André?

Chapter 16

§§ 158, 159.--a. Why was the scene of action

transferred to the South? b. What places were captured?

c. Compare the British and American armies at Camden. What

was the result of this battle?

§§ 160-163.--a. Describe the battle of King's

Mountain. b. What was the result of the battle of the

Cowpens? c. Follow the retreat of the Americans across North

Carolina. What events showed Greene's foresight? d. What

were the results of the battle of Guilford? e. Compare the

outlook for the Americans in 1781 with that of 1780.

§§ 164-166. a. How did the British army get to

Yorktown? b. Describe the gathering of the Allied Forces.

c. Describe the surrender and note its effects on America,

France, and Great Britain.

§ 167.--a. Where were the negotiations for peace

carried on? b. Mark on a map the original territory of the

United States. c. How did Spain get the Floridas?

General Questions

a. When did the Revolution begin? When did it end?

b. Were the colonies independent when the Declaration of

Independence was adopted? c. Select any campaign and discuss

its objects, plan, the leading battles, and the results. d.

Follow Washington's movements from 1775-82. e. What do you

consider the most decisive battle of the war? Why?

Topics For Special Work

a. Naval victories. b. Burgoyne's campaign.

c. Greene as a general. d. Nathan Hale. e. The

peace negotiations.

Suggestions

The use of map or molding board should be constant during the

study of this period. Do not spend time on the details of battles,

but teach campaigns as a whole. In using the molding board the

movements of armies can be shown by colored pins.

The Declaration of Independence should be carefully studied,

especially the first portions. Finally, the territorial settlement

of 1783 should be thoroughly explained, using map or molding

board.

|